Microeconomics

Demand and Supply

Demand: The willingness or ability of a consumer to purchase a certain good or service at any given price at any given time.

Supply: The willingness or ability of a producer to purchase a certain good or service at any given price at any given time.

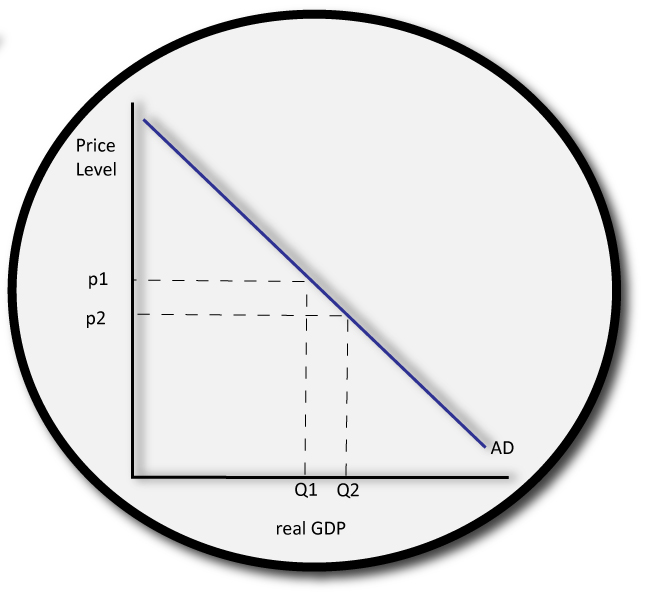

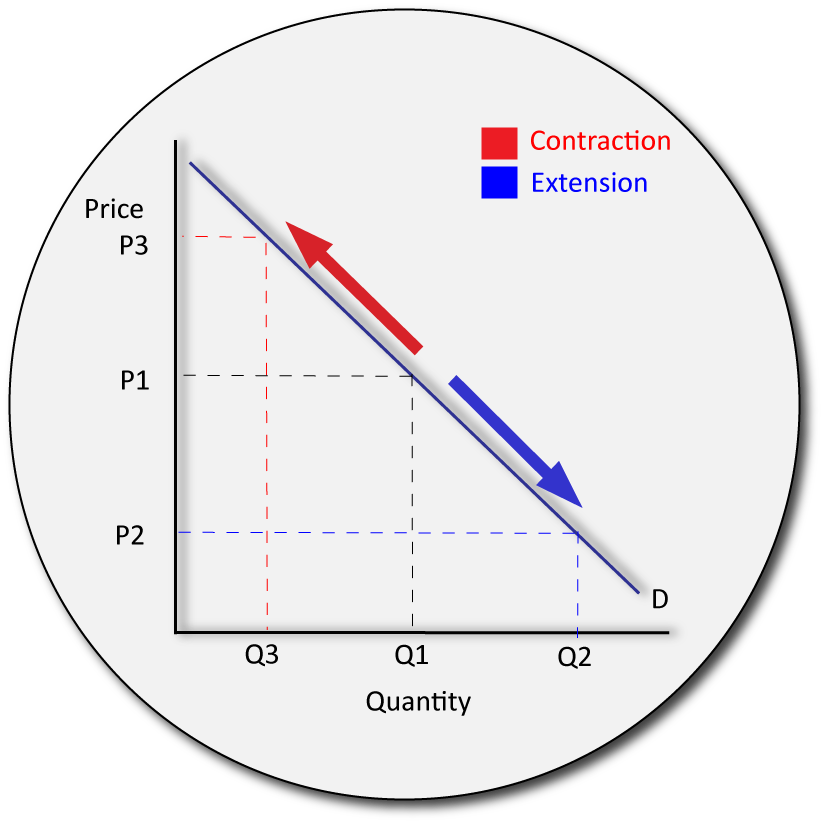

Relationship between Demand and Price

As price increases, we desire to buy less goods and services; there is an inverse relationship between the amount (quantity) demanded and the price. This is known as a contraction in demand.

As price falls, we desire to buy more goods and services; there is an inverse relationship between the amount (quantity) demanded and the price. This is known as an extension in demand.

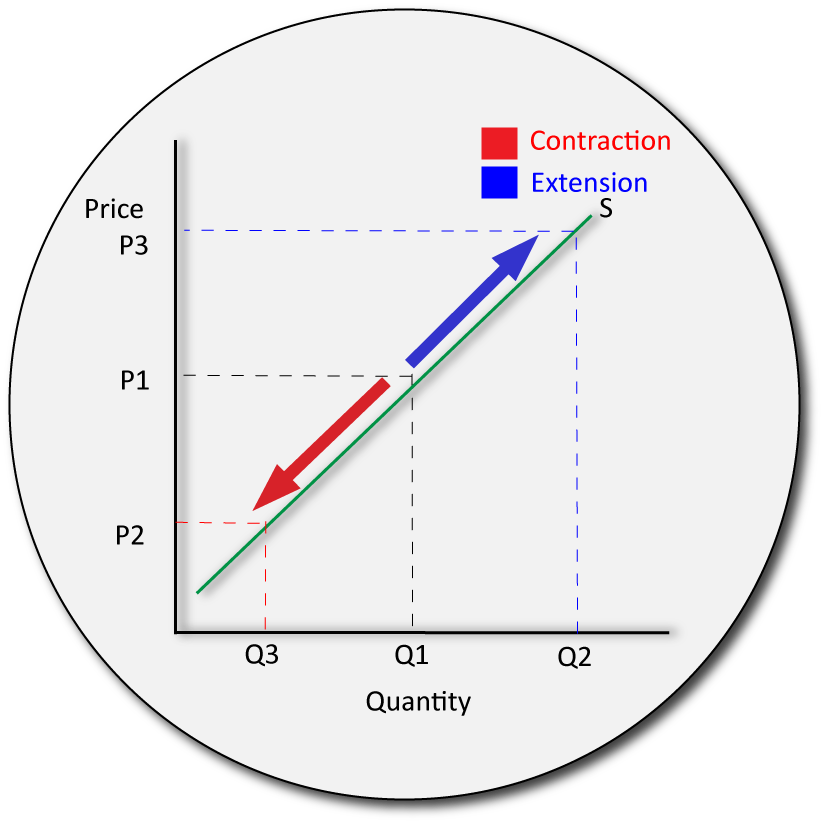

Relationship between Supply and Price

As price increases, we wish to sell more goods and services; there is a direct relationship between the amount (quantity) supplied and the price. This is known as an extension in supply.

As price falls, we wish to sell less goods and services; there is a direct relationship between the amount (quantity) supplied and the price. This is known as an extension in supply.

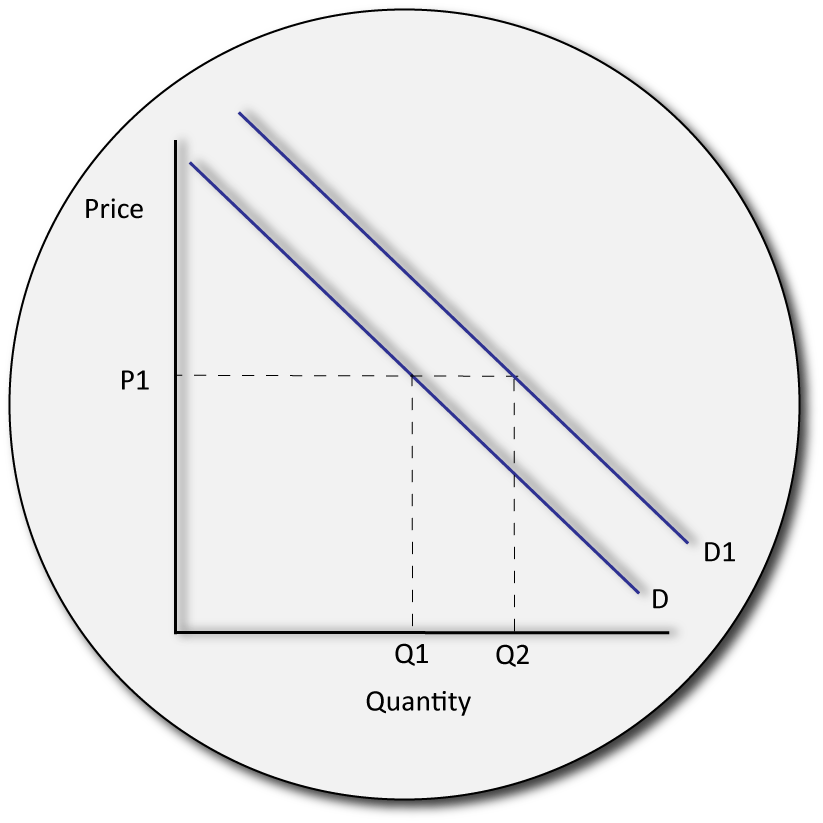

Shifts in Demand

Any factor (or 'determinant') that causes us to want more or less, even though price has not changed, causes a shift in our entire demand curve. This is autonomous of price.

Determinants of demand include:

- changes in income,

- changes in direct taxation,

- changes in fashion,

- changes in population,

- future predictions,

- the price of substitute or complementary goods

- changes in perceived wealth.

When we consume more even though price has not changed this is an increase in Demand, and shown as an outward shift of the curve. (D-D1 on the diagram to the right)

When we consume more even though price has not changed this is a decrease in Demand and shown as an inward shift of the curve. (D1-D on the diagram to the right)

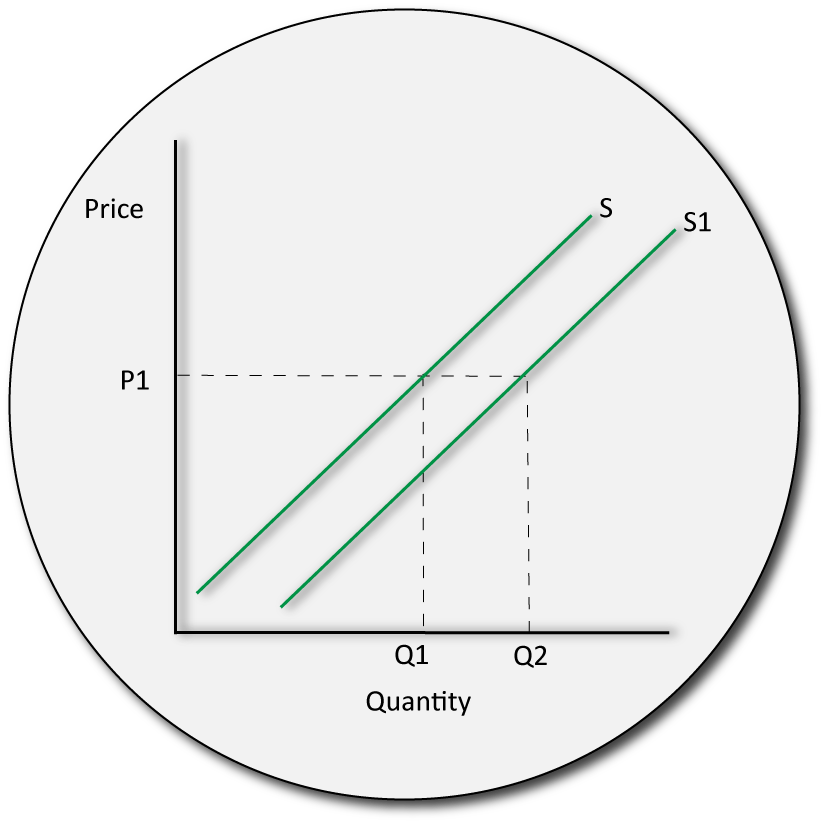

Shifts in Supply

Any factor (or 'determinant') that causes producers to supply more or less, even though price has not changed, causes a shift in our entire supply curve. This is autonomous of price.

Determinants of supply include: changes in weather, changes in business taxation, changes in the costs of production and changes in red tape

When we supply more even though price has not changed this is an increase in Supply, and shown as an outward shift of the curve. (S-S1)

When we supply more even though price has not changed this is a decrease in Supply and shown as an inward shift of the curve (S1-S)

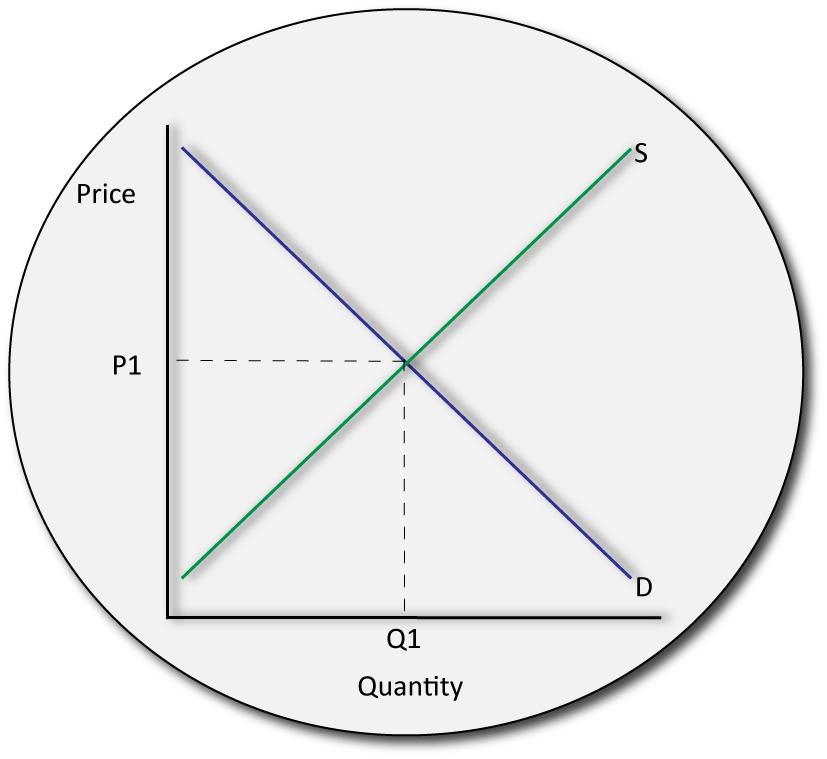

Equilibrium

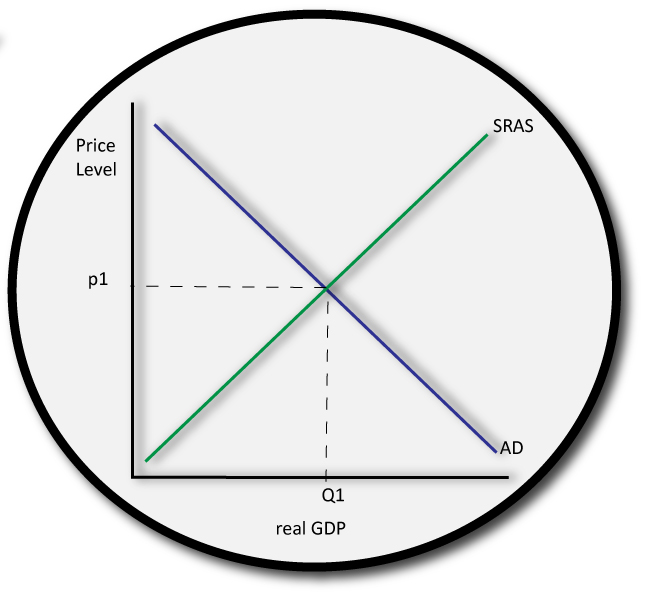

When producers agree to sell at a price that consumers are willing to buy at, this is known as equilibrium or market clearing price (P1 on the diagram to the right)

Shifts in Demand or Supply cause equilibrium price to change; this is known as the price mechanism, as explained below.

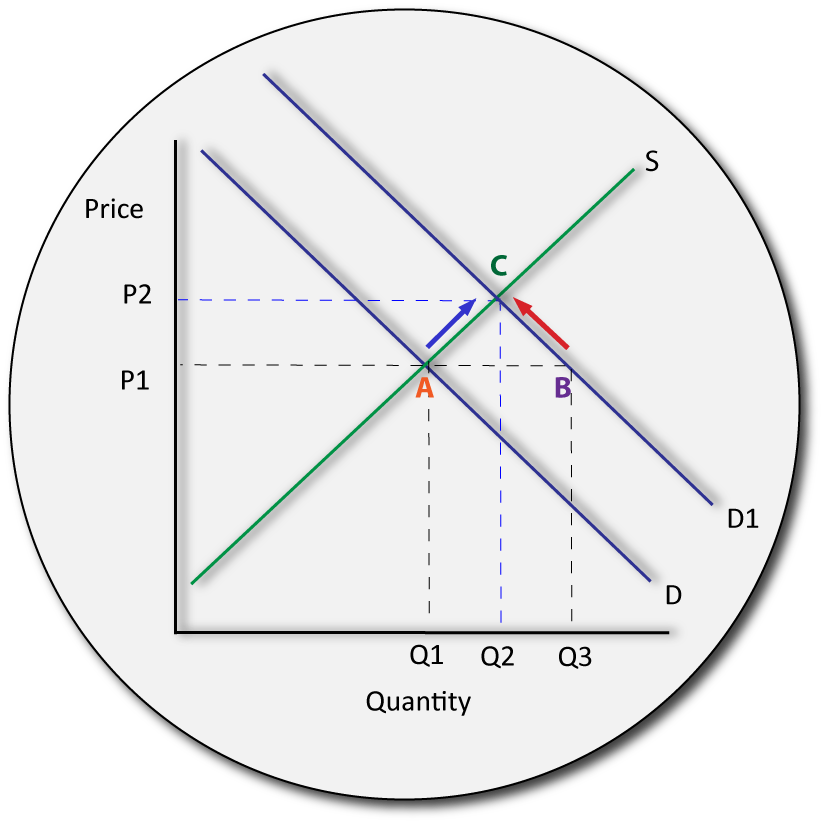

The Price Mechanism

Price acts as a signal and incentive to producers and consumers. Once equilibrium price is established both consumers and producers are content. However, a change in Demand or Supply will have knock on effects.

Imagine we are at Point A (Equilibrium starting price).

In this scenario lets say we are talking about the demand and supply of wheat.

If there happened to be really good weather one month, then wheat suppliers may experience an increase in the amount of wheat they can sell. Supply has shifted outwards (S-S1)

In the immediate run, if producers continue to sell at the original price, they will find that there is too much wheat on the market and that demand has already been satisfied (Point B). There is excess supply.

Instead, in order to get rid of the wheat, they must drop their prices. Wheat is now less valuable.

A change in price, however, alerts consumers. According to the Law of Demand, when price falls, consumers' demand extends.

At the same time, some producers find that it is no longer profitable to supply at this decreased price and so no longer grow wheat. Our allocation of resources has changed.

We thus end up at Point C; a new market equilibrium.

Price has acted as a signal and incentive on what to consume and produce. Price mechanisms work for any shift in demand and supply.

Excess Demand

This refers to when price remains below equilibrium, thus causing consumers to want more than is supplied. Producers will realise that they can raise the price of their product, causing a contraction in demand and a return to equilibrium

Excess Supply

This refers to when price remains above equilibrium, thus causing consumers to want less than is supplied. Producers must then drop the price of their product in order to get rid of it, causing an extension in demand and a return to equilibrium.

Applied Economics

Ever since the dawn of time, Man has always had a hankering for gold. Initially used as a form of payment, it is gold's scarcity that makes it so attractive. For example, the Spanish conquistadors were initally more interested in silver, but once they realised that by hoarding so much out of South America, they caused its value to plummet, it was gold that once again rose to prominance. The fact that it is impossible to create, and very hard to find, means that demand for gold is always high.

In fact, since 2008, gold has continued to see a resurgance in popularity - this was mainly because people began to lose faith in banks and investments, so turned instead to the shiny metal. The effect of this increase in fashion? Soaring prices of gold, of course. As of 2013, $1324/oz. Before the 1970s, all currencies were 'pegged to gold' to give them real value - for example, if you lived in the UK you could go to the bank and exchange your Pound Sterling, for a pound of gold. This will be explored later in Unit 3.

Exceptions to Demand

Several goods 'defy' the Law of Demand and have a direct relationship with price instead of an inverse one.

1) Veblen Goods -experience a direct relationship between price and quantity demanded. This is owing to 'snob-value'; a phenomenon which states that a higher price is indicative of a more expensive good, and therefore improves your social standing. Diamonds are often cited as an example; if the price of a diamond were to rise, people may want more, as they would be seen as of a higher class for buying the expensive ones.

2) Giffen Goods- although controversial amongst economists, Robert Giffen argued that certain goods in poor income families had a direct relationship between price and quantity demanded. If you take bread (or any staple) as an example: Imagine a poor family buys 3 loaves of bread and some chicken. The price of bread begins to rise. Now they can't afford the 3 loaves but must make a choice between continuing to buy the food that will sustain them (the bread) or buying less of it and continuing with the more luxurious product (the chicken). Clearly they will choose the bread and give up the chicken. With the leftover money they will continue to buy bread to make up for the chicken.

3) Goods with Expectations - as the price of some shares and stocks rise, people want more of them - as long as they believe the price will continue to rise. This is because they feel that buying more of the product at a rising price may give them better returns in the future. They expect the shares to continue rising and thus buy more of them. On the other hand, as the price of shares fall, people want less of them if they believe that its value will continue to fall. Price and Quantity Demanded are thus directly related.

Exceptions to Supply

Several goods 'defy' the Law of Supply as they have a limited relationship with price.

1) Goods/services with limited capacity - concerts can only hold a certin amount of people. It is impossible to put more than the seated capacity into the venue. Supply is thus perfectly inelastic. It is fixed and cannot be changed. Similarly, domestically, the amount of money in the economy is fixed by the government; we cannot print more even if we want to.

2) Goods that are no longer produced - you cannot reprint a famous stamp or produce more Roman coins. These goods are fixed in supply owing to the fact that it is impossible to reproduce them.

Linear Demand and Supply

Linear Demand and Supply Equations

- Linear Demand equations help us construct a demand curve using the following formula.

- Qd = a - Bp

- To work out the demand curve we do the following:

If Qd=100 - 25p

- First we set Qd as 0, we can work out what price would be. so:

0 =100-25p

25p=100

1p=4

When Qd is 0 then p is 4.

- We then go back to the equation and now set price as 0

- Qd = 100-0

When P is 0 then Qd is 100. This can now be plotted

General Rules

When the a variable remains constant but the B variable changes, we see a change in gradient/elasticity

When the B variable remains constant but the a variable changes, we see a shift in demand

Linear Supply Equations

- Supply Linear Equations—We know that price and quantity have a positive relationship for supply We can now also see how to plot this using a linear demand formula: Qs = c+dP

First, draw the axis for a supply diagram.

Then, look at your equation (example: Qs= —30+20p)

Let’s assume we want to know price (p)

We need to rearrange the equationQs= —30+20p

Let’s assume QS=0.If that were true then we have the formula: 0 = —30+20p

But this is unbalanced. To balance it we move —30 across, our equation becomes +30 = 20p

To find P when QS is 0, we must therefore divide 30/20 =1.5Once we know price we need to go back and find out Qs

Qs= —30+20p

To do this, we got back to the original equation and set P at 0Qs=—30+0

Qs= —30

So we know that:

When QS is 0 then P = 1.5

When P is 0 then QS = —30

So plot your curve!When the c variable remains constant but the d variable changes, we see a change in gradient/elasticity

When the d variable remains constant but the c variable changes, we see a shift in supply

Finding Equilibrium

- To find equilibrium simply do the following: take the two equations and solve them!

- e.g: Qd =100 - 25p; Qs = —30+20p

100-25p = - 30 + 20p

130 = 45p

p = 2.89

- We then take equilibrium price, drop it into either the Qd or the Qs equation and calculate equilibrium quantity. e.g.

Qd = 100 - 25(2.89)

Qd = 78

- So at equilibrium, price is 2.89 and quantity is 78

Allocative Demand and Tax Burdens

Consumer surplus can be defined as the satisfaction a consumer gains from not having to pay the price he or she was originally willing to pay. Instead, by paying the lower market (or equilibrium) price, he or she 'gains' the difference.

Producer surplus can be defined as the satisfaction a producer gains from not having to sell at the price he or she was originally willing to sell out. Instead, by receiving the higher market (or equilibrium) price, they 'gain' the difference.

Efficiency

Marginal Benefit the benefit a consumer gets from a product increases as price falls

Marginal Cost the cost to a firm of producing the next unit

Efficiency - producing using all of our resources to the maximum

Allocative Efficiency - this is where consumer and producer surplus are maximized as what is produced is reflective of society's wants. All resources are allocated according to what is demanded and can be supplied. It should also occur where p=mc (see unit 1.3 for more on this)

Productive Efficiency - where firms produce the maximum possible amount using the least amount of resources.

Economic Efficiency - where allocative and productive efficiency are met accross all markets in an economy.

Different Elasticities

Elasticity measures the responsiveness between two variables when one is changed.The Types of Elasticity

- 1. Price Elasticity of Demand

- 2. Income Elasticity of Demand

- 3. Cross Elasticity of Demand

- 4. Price Elasticity of Supply

Each of these elasticities is useful for producers for differing reasons.

Price Elasticity of Demand

Price Elasticity of Demand—measures the responsiveness between a change in price and the effect on quantity demanded. Measured using formula below.

Price Inelastic

—tells us that a great change in price results in a small change in quantity demanded. Has a PED of <1. Usually goods with low starting price or necessities

Price Elastic

—tells us that a small change in price results in a large change in quantity demanded. Has a PED of >1. Usually luxuries or goods with many substitutes

Varying Price Elasticity of Demand—all demand curves show us varying degrees of elasticity at different price ranges. We cannot use a single demand diagram to show us elasticity in general; it must be at a specific price. Only if demand curves share a price range and intersect each other can they be compared—and even then, only at that price.

Reasons why PED is important

- Revenue Maximization—Revenue = PxQ. Producing at Unitary Price Elasticity = greatest total revenue.

- Price Discrimination— different people have different PED’s for certain products; we can maximize revenue totally by targeting different prices at different people.

- Tax maximization—To maximize taxation revenue—taxing inelastic goods producers higher government revenue

- Commodity Agreements—To ensure fair prices for commodity producers— decreasing supply = increasing TR for commodity growers—this is illogical and must be corrected

Income Elasticity of Demand

YED (Income Elasticity of Demand)

Theory: measures the relationship between a change in income and the change in demand for a product

Example: Changing incomes

Effect: The greater the positive result, the greater the shift outwards. If it is negative this indicates inward shift (and thus inferior goods)

Equation: YED = % Change of Income / % Change in Demand for Good X

Can be shown with income on Y axis, and Demand on X axis

Reasons why YED is important

- To identify sectoral change

- For investment purposes

- To show why government intervention is needed for commodity producers

Cross elasticity of Demand

XED/CED (Cross Elasticity of Demand)

Theory: measures the relationship between a change in price for one product and the change in demand for another

Example: Coke and Pepsi, Cars and Oil

Effect: The greater the positive number, the more the good is substitutional. If the number is negative, they are complements

Equation: CED = % Change of Price for Good X / % Change in Demand for Good Y

Reasons why CED is important:

- To understand internal pricing

- To understand impact on rivals

- To decide whether to merge

- To prevent from external shocks

Price Elasticity of Supply

Theory: measures the relationship between a change in price and the change in supply for a productExample: Growing wheat.

Effect: The greater the result the more elastic supply is. If the number is <1 it is inelastic, >1 elastic.

Equation: PES = % Change in Price for Good X / % Change in Supply for Good X

Reasons why it is important:

Shows how quickly producers can react to a change in price.

Inelastic Supply

elastic Supply

Revenue and Elasticity

Revenue and Elasticity

- Between two prices every Demand curve actually has 3 sections: an elastic, inelastic and unitary elastic section.

- If producers calculated their product's elasticity they would be able to know where to set the price to maximize revenue.

- The upper section (from the middle upwards) of a Demand curve is the elastic section. Along this section, if producers attempted to increase price, they would see quantity demanded of their product fall by a greater amount. Since Revenue is Price x Quantity, if quantity falls by a greater amount than price rises, revenue will be lost.

- Along this section the producer must thus decrease prices to increase revenue (a fall in price will correspond to a greater increase in quantity demanded; thus increasing revenue)

- The lower section (from the middle downwards) of a Demand curve is the inelastic section. Along this section if producers attempted to increase price, they would see quantity demanded of their product fall by a smaller amount than the price increase. Since Revenue is Price x Quantity, if quantity falls by a smaller amount than price rises then revenue is gained.

- Along this section the producer must thus increase prices to increase revenue.

Tax and Elasticity

Price Elasticity of Demand and Tax

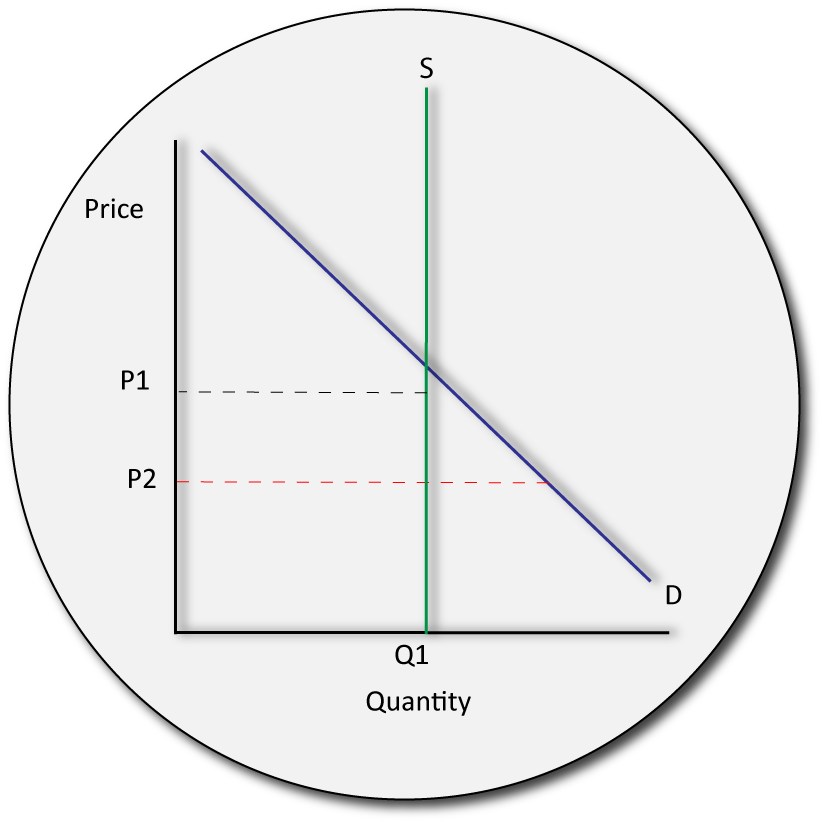

Knowing the Price Elasticity of Demand and Supply for our product is very useful for the government too. By working it out, they can decide on how much tax to charge. Let's look at the first diagram.

Demand here is price inelastic (<1). What happens then, when a tax - (remember, tax is a determinant of supply and thus shifts it inwards because it is more expensive to produce) - is placed on the product?

Now let's have a look at diagram 2 and at what happens if demand is price elastic (>1) and we put that tax on.

Clearly in this example we lose 30% of our product for 10% incraese in price. Q1xP1 is thus smaller than Q2xP2. Whilst the government does till get tax, this tax is lower than for an inelastic good.

Elasticity, Taxation and Consumer/Producer Burden

What about if we wanted to find out who was affected most by these taxes? We call this the tax burden - the section of society that pays for most of the tax. In an ideal world for producers, if the government put a 10% tax on a good, then they would charge 10% more for their product. They would actually then pay none of the tax, the consumer would pay it all. But to do this, their PED would have to be perfectly inelastic... unlikely.

- The way we calculate where the burden of tax falls is simple. Draw in P1 and Q1. Then draw in the effect of the tax (S-S1). Then, at the new equilibrium (marked A) draw a dotted line down to the original supply (B). The difference betwen A and B is the value of the tax.

- But B is lower than the original price. This area (green) is thus the amount of tax the producer pays. The difference between P1 (original price) and the new equilibrium price (which you can label P2) is the amount of tax WE pay.

Overall Rules

- When demand is price inelastic and a flat rate tax is imposed, the greater the consumer burden of tax- we say that the incidence of tax falls on the consumer.

- When demand is price elastic and a flat-rate tax is imposed, the greater the producer burden - we say that the incidence of tax falls on the producer.

- The more inelastic the product, the more the consumer pays the burden of tax and vice-versa.

Price Ceilings, Floors and Buffer Stock Schemes

Price Ceilings - when price is not allowed to rise above a certain limit. If set below equlibrium, this is known as a constraining price ceiling; if not, it will have no immediate effect.

Price Floors - when price is not allowed to fall below a certain limit. If set above equlibrium, this is known as a constraining price floor; if not, it will have no immediate effect.

Effects of a Price Floor

Black Markets may occur as producers seek to get rid of excess stock

Misallocation of resources - we experience excess supply

Storage problems - if done with agricultural products, we have difficulties keeping them products from going to waste

Increased income for producers, making them better off

Higher prices for consumers, causing a lack of demand

Avoidance - producers may try and avoid the price ceiling by sub-dividing products (e.g. housing if there is a price floor on rent)

Effects of a Price Ceiling

Long queues and lines - consumers greatly desire the product at such a low price

Lack of supply - producers gain less revenue from their product and so supply less as a result.

Black markets - consumers are so willing to buy the product they may offer a little more money in exchange for the good

Non-price allocation of resources - such as favouritism occurs, as there are few goods

Buffer Stock Schemes

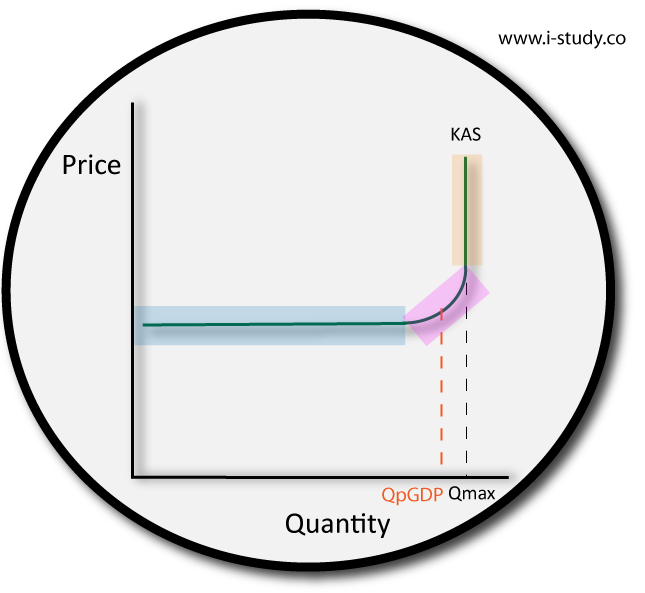

Producers of commodities often face volatile (changing) prices owing to fluctuations (changes) in supply because of weather patterns. For example, rice grows very well when there are heavy rains, but suffers greatly if there is a dry season. As a result, it is very difficult for farmers to plan their incomes and lives when supply (and therefore revenue) is constantly changing.

It is obviously very bad for society if farmers start deciding to not grow crops owing to its fluctuating prices. Instead, in order to make sure enough is grown at a fair price, the government may step in and implement a buffer stock scheme. These became very popular amongst developmental economists in the 1970s, in developing countries, but have since faded in popularity.

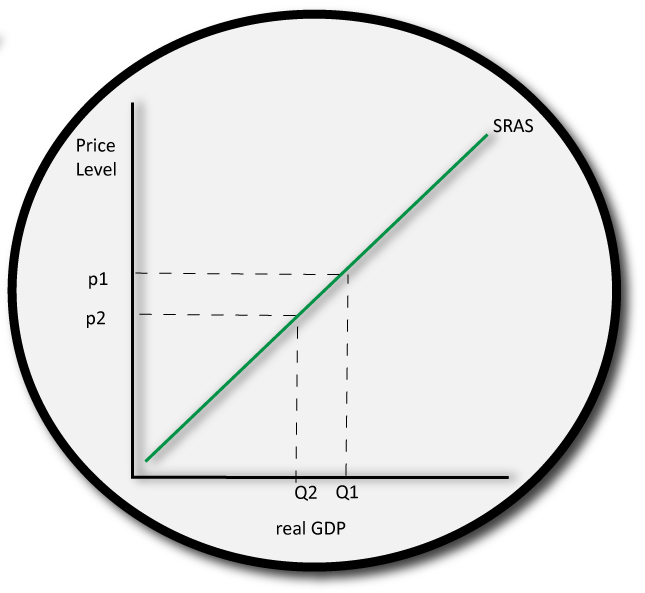

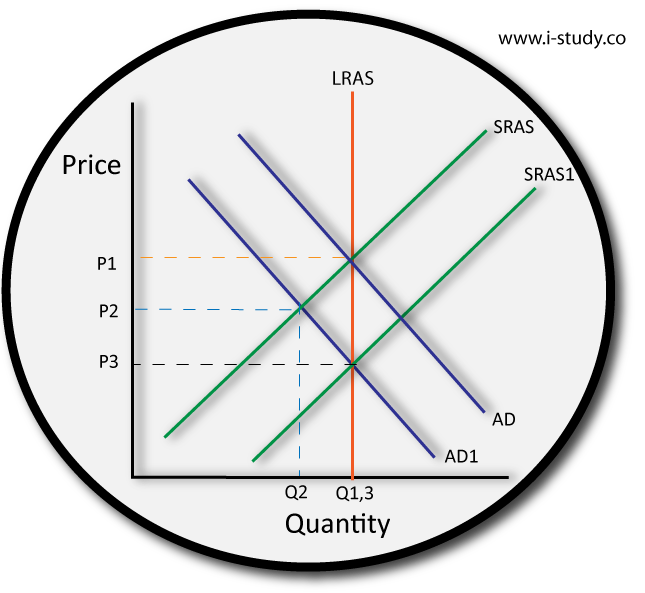

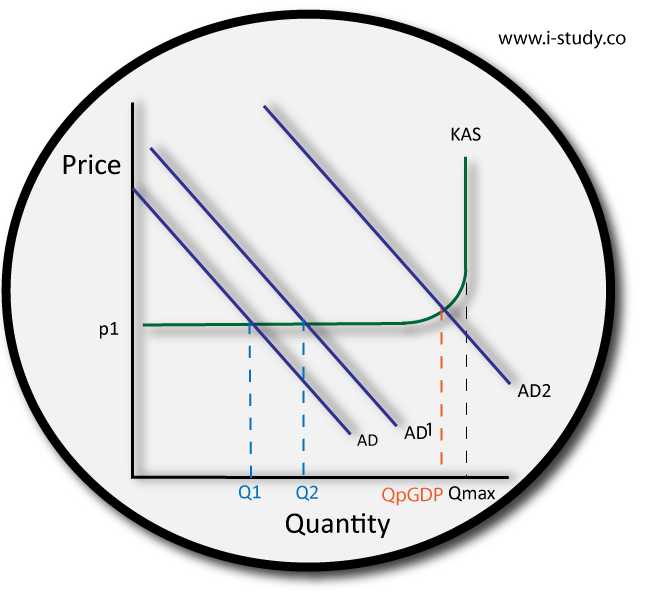

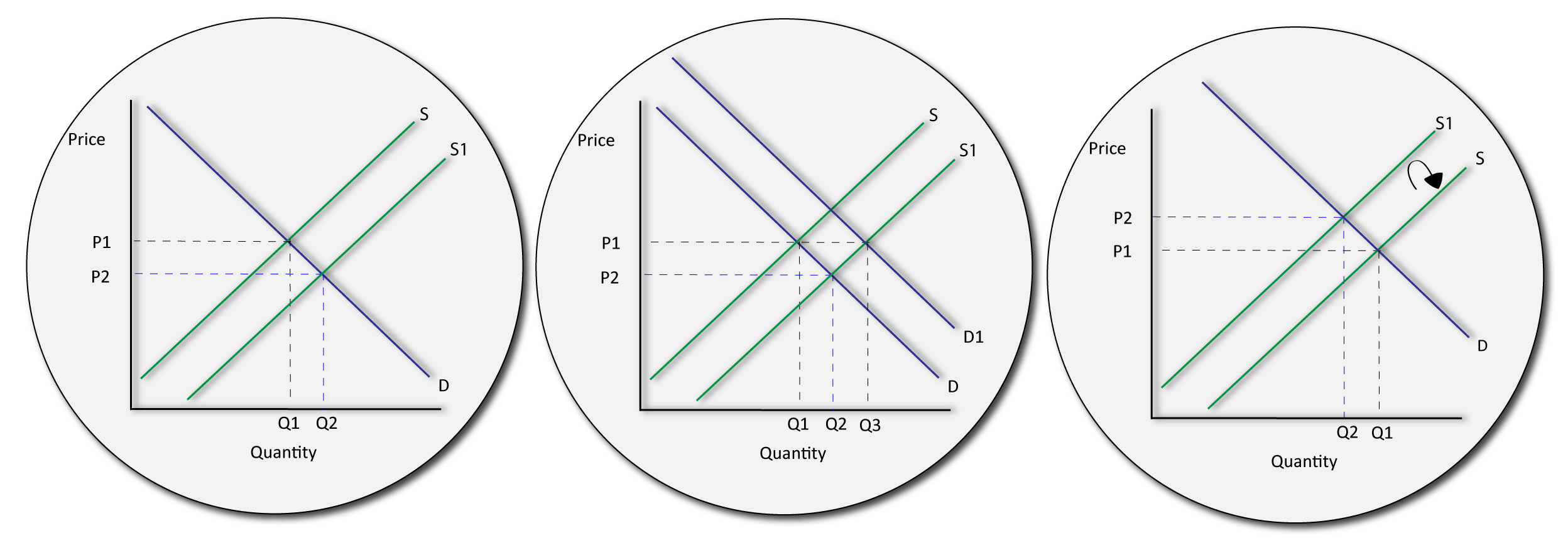

The way the schemes work depends upon many assumptions. Let us imagine that we are a rice grower and there has just been heavy, heavy rains. Supply has increased greatly and therefore, on diagram 1 below, prices fall from p1-p2 and our revenue also falls. The government though, signs an agreement with us beforehand to promise that no matter how great the increase in supply, they will guarantee us Price 1.

In order to fulfill their promise, the government then buys a lot of our rice, forcing demand back up and regulating prices. We are therefore back at p1 in our second diagram.

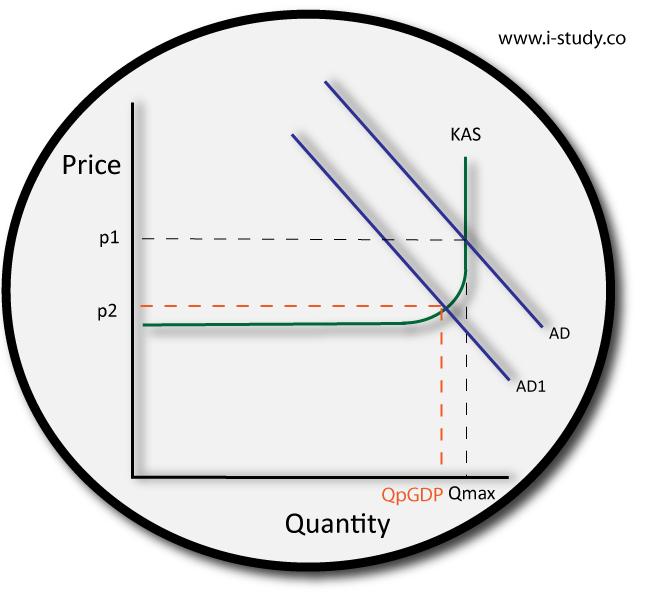

The next year, when a bad harvest occurs due to, say, bad rains (S-S1), prices rise. But again, the government promised us p1 and so releases all the rice it previously bought back onto the market (S1-S on diagram 3). This has the effect of lowering prices back to the agreed price and gets rid of the government's stored rice too. In this way prices have been regulated to ensure they are stable.

Problems with Buffer Stock Schemes

- Storage

- Continuous years of surplus or of bad weather

- Allocative and Productive Inefficiency

- Calculating Demand

- Agreeing an original price and time

- Government Debt and Opportunity Cost

Calculating Burdens and Subsidies

Calculating Burdens with a Tax

Indirect Tax - a tax on a good or service. Includes:

Ad Valorem Tax- a tax charged as a percentage

Flat Rate Tax - a tax charged as a specific value

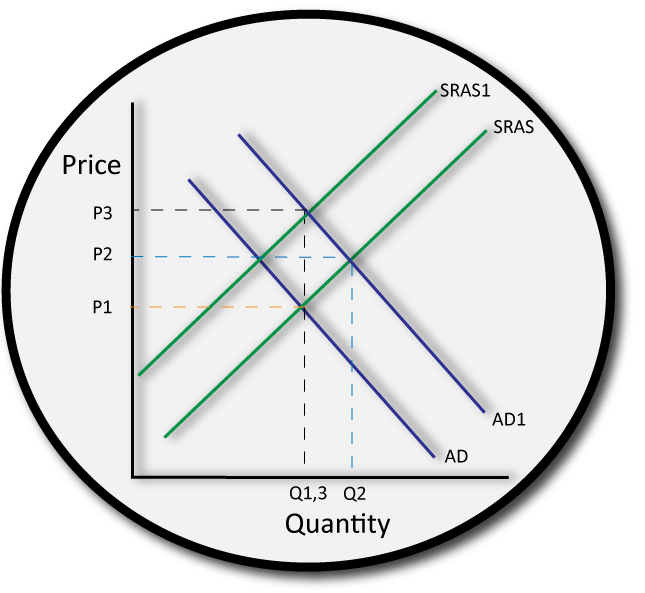

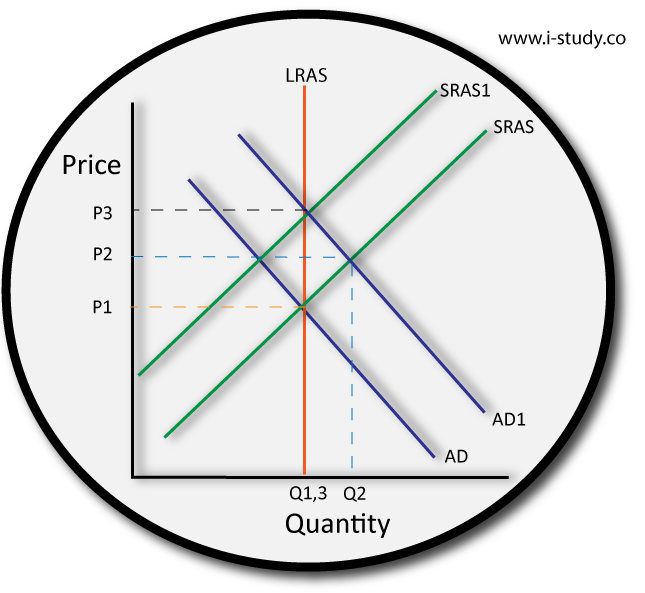

- When a tax is imposed each unit of production is more expensive to produce

- This is because costs of production have now risen

- As a result, less is produced; there is a shift in supply (S-S1)

- The value of the tax per unit is the vertical difference between the two supply lines

- We calculate this by first marking on the original equilibrium price (p1)

- Then, we shift supply inwards to show a fall in production

- The vertical difference starting from the new equilibrium shows us the value of the tax

- The red area shows us the difference between the new price (p2) and the old price (p1)at the new quantity for the consumer. This is their new, reduced, consumer surplus.

- The green area shows us the difference between the new price gained (p2) and the rest of the tax (p3)

- Clearly in this case the consumer has paid some of the tax burden, whilst the producer has paid the rest.

- The amount of tax paid depends on the products' elasticity (see unit 1.2)

Understanding Market Failure

- Market failure can simply be defined as the process by which the free economic market, when left to demand and supply, fails to correct problems that the system generates.

- These 'problems' are called 'externalities' and can be defined as when a third party - someone who was not involved in the original action - is harmed or overally benefited by that action.

- There are different types of externalities. Negative externaliteis are harmful to third parties, positive externalities are unfairly beneficial.

- If the externality is caused by us - the consumers - it is a consumption externality. If it caused by a producer it is a production externality.

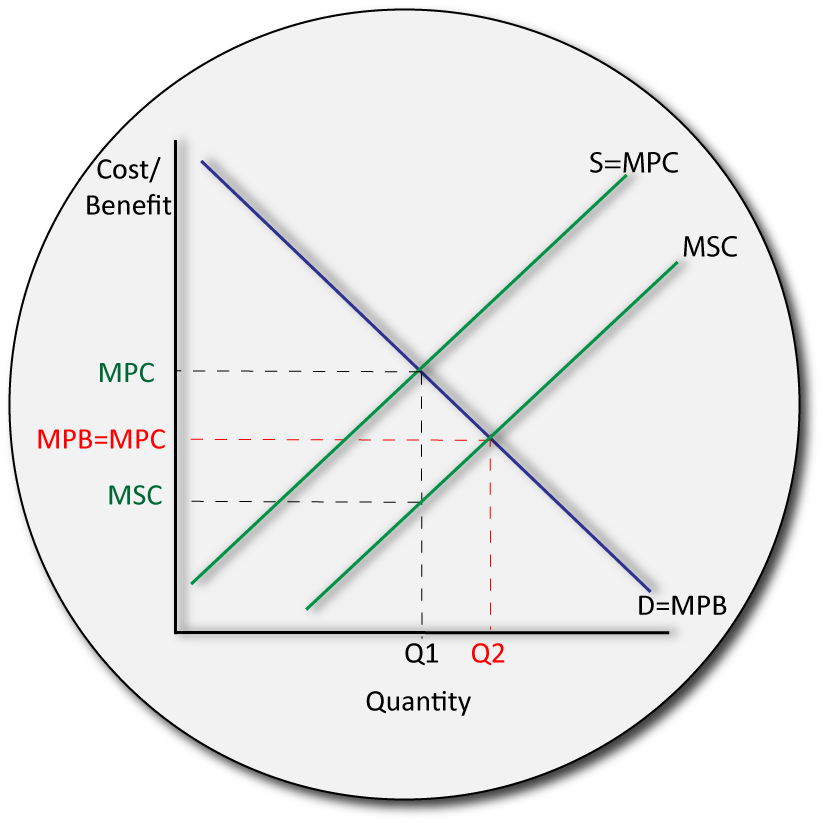

To understand how to draw externalities on a diagram we change our demand and supply a bit and re-interprate it.

Demand - how much we are willing to pay - becomes our Marginal Private Benefit (if we were willing to pay $10 for a t-shirt, the benefit we get from it can be shown as $10)

Supply - how much we are willing to produce - becomes Marginal Private Cost.

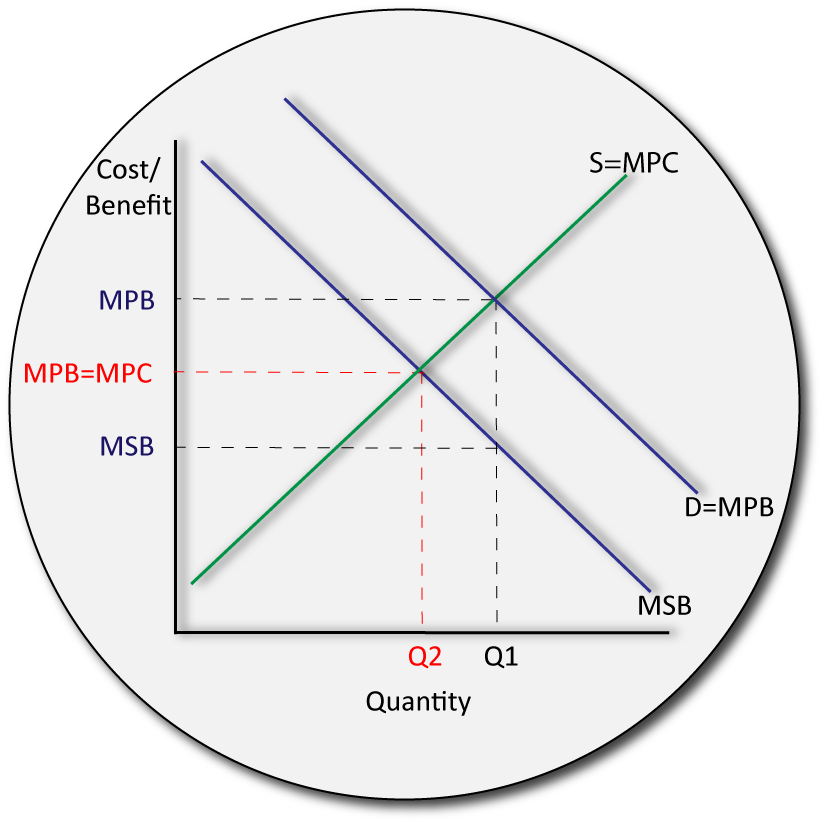

This is seen in the diagram.

Negative Externalities

Negative Consumption Externalities (NCE's)

Explanation: When consumers buy a cigarettes, the benefit to society is lower than the benefit to the individual (in this case, society is harmed by all the second-hand smoke).

There is a separation between Private Benefit and Social Benefit. If a good benefits the individual more than society, the individual’s satisfaction is coming at the cost to society.

In other words, MPB is lower than MSC. We need to encourage less people to buy these products.

There is an over-allocation of resources so we are not being allocatively efficient. We should be at Q2, but are at Q1.

Methods to address this: Advertising, Taxation, Legislation

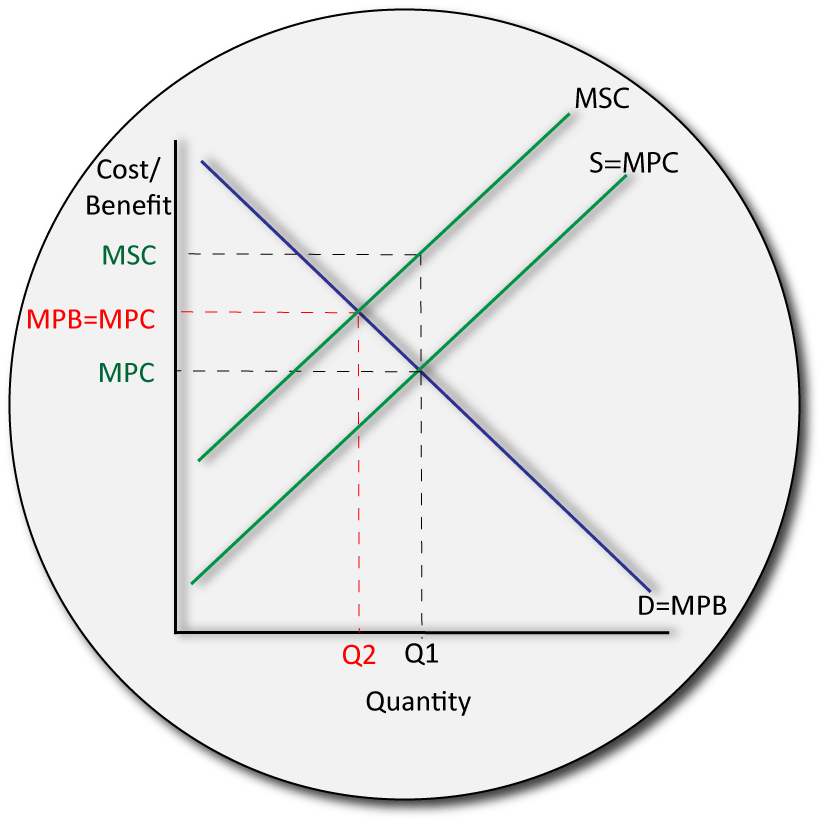

Negative Production Externalities (NPE's)

Negative Production Externalities.

Example: Pollution.

Explanation: When a firm pollutes, the cost to society (in the form of all the healthcare costs) is greater than the private cost to the firm. The firm does not care about the pollution, but everyone else suffers. Society wants us to produce much less (Q2) but we are over-producing this good (Q1). There is a separation between MPC and MSC. We need to find a way to correct this.

Methods to address this: Pigovian Taxes, Trading Permits, Laws, Property Rights

Positive Externalities

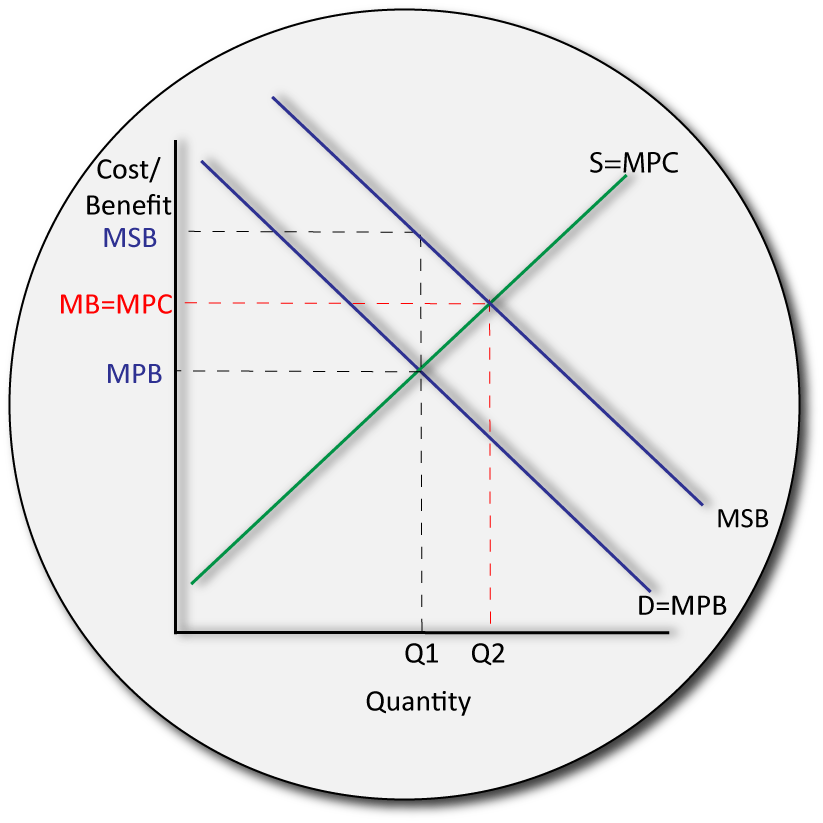

Positive Consumption Externalities (PCE's)

Positive Consumption Externalities.

Example: Buying a hydro-electric car

Explanation: When consumers buy a hydro electric car, the benefit to society is greater than the benefit to the individual (in this case, society benefits from all the clean air). There is a separation between Private Benefit and Social Benefit. If a good benefits society more than the individual, the individual will not be inclined to buy as much of it as society likes, as his personal satisfaction is not great enough. In other words, MPB is lower than MSC. We need to encourage more people to buy these products. There is an under-allocation of resources so we are not being allocatively efficient. We should be at Q2, but are at Q1.

Methods to address this: Advertising, subsidies, legislation

Positive Production Externalities (PPE's)

Positive Production Externalities.

Example: Research and development of drugs.

Explanation: When producers pay millions of dollars to discover a new way of doing something, then all of society benefits greatly. However, the firm itself paid a high cost (millions of dollars) for the research. If everyone gets more benefit from the research than the firm itself, it is unlikely to continue doing such research. There is a sepeartion between the cost to the individual firm, and the cost to society. We need to somehow encourage the firm to continue producing their goods as society wants Q2 but we are only at Q1. There is an under-allocation of resources so we are not allocatively efficient.

Methods to address this: Subsidies (increases S=MPC so that S=MPC=MSC)